Politicization of Soft News in Times of Crisis: Media Coverage of the Eurovision Song Contests, 2023–2025

Gilad Greenwald

Greenwald, G. (2025). Politicization of Soft News in Times of Crisis: Media Coverage of the Eurovision Song Contests, 2023–2025. Media Frames, 27, 191–224. https://doi.org/10.57583/MF.2025.27.10088

Abstract

This article examines the politicization of soft news in Israel, through an analysis of the Eurovision Song Contest coverage during the years 2023-2025, against the backdrop of the Gaza war. Adopting a perspective of the media as a hybrid arena, where the boundaries between hard and soft news are often blurred, the study explores how an event commonly perceived as cultural and entertaining is covered during times of tension and crisis. The research is based on a combined quantitative and qualitative analysis of 328 news items from three major Israeli digital news outlets: Haaretz, Israel Hayom, and Ynet. The quantitative findings indicate a sharp increase in the political framing of Eurovision as the military conflict escalated, alongside a continued presence of sensational, gossip-oriented, and escapist framings. The qualitative analysis sharpens the dynamic between entertainment-driven drama and the symbolic processing of collective anxiety, highlighting the transformation of soft news topics into a space in which national tensions and political identities are shaped and interpreted. The article contributes to the understanding of the media’s shifting role in times of crisis and offers a renewed perspective on soft news as a significant arena for “serious” public and political engagement, particularly during such periods.

Introduction

The Gaza war broke out in October 2023, following Hamas’s terrorist attack on Israeli civilians and soldiers. The October 7 assault is widely regarded as the most devastating and traumatic event in Israel’s history, due to its unprecedented toll — 1,163 murdered and killed, many of them civilians, including infants, children, women, and the elderly — alongside the abduction of 251 Israelis to the Gaza Strip. The event was marked by complete surprise and a profound systemic failure, both at the security and governmental levels (Weimann-Saks et al., 2024).

In the war that ensued, tens of thousands of Palestinians and thousands of Lebanese were reportedly killed, and hundreds of thousands were wounded (Lev-On & Gozansky, 2024). The war’s persistence and its humanitarian toll provoked harsh international criticism of Israel and intense anger toward its policies, even from countries traditionally viewed as allies. Among other repercussions were efforts to prosecute senior Israeli officials at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. According to public opinion surveys conducted in various countries, Israel’s global image in 2024–2025 ranked among the worst in its history (World Population Review, 2025).

It appears that the day of the massacre, the war that erupted in its aftermath, the ongoing struggle to bring the hostages home, and the sharp international criticism directed at Israel—in global diplomacy as well as in international media—have shaken Israeli society with exceptional force and depth. One of the most notable effects of these events, at least during the initial period following the outbreak of the war, was a dramatic surge in news consumption among the Israeli public. This trend, noted as well in previous wartime contexts (Malka et al., 2015), manifested with even greater intensity in the present case. News broadcasts became significantly longer, and coverage of “hard news,” particularly foreign affairs, politics, and security, increased substantially (Weimann-Saks et al., 2024).

The central aim of the present article is to identify and analyze the phenomenon by which even “soft news” — particularly entertainment events such as the Eurovision Song Contest — have become increasingly politicized in their presentation and framing under the shadow of war. Traditionally, soft news includes areas such as leisure, culture, and entertainment, and is generally positioned at the periphery of the news agenda, given its classification as content less central to the essential functioning of society (Meeks, 2012). However, previous studies have shown that journalists covering entertainment and celebrity news may also draw upon political or security-related themes as a means of attracting public attention to their fields of coverage. This practice is especially relevant in countries like Israel, where public opinion is politically engaged to a large degree, and political participation is regarded as a civic duty (Greenwald, 2020).

In 2024 and 2025, the Eurovision Song Contests were marked by an unusually high level of politicization. This stands in clear contrast to more “normative” years in the contest and its media coverage—such as 2023—which were not politically charged, either in the Israeli context or more broadly. The heightened politicization of Eurovision during these two years, compared with 2023, manifested in calls by several participating countries to boycott or suspend Israel in response to the war in Gaza. These calls translated into overt hostility toward the Israeli delegations and performers: from parts of the live audience—some of whom, at an unprecedented scale, accompanied Israel’s performance with sustained and thunderous booing; from other delegations, artists, European broadcasters, and national jury members; and from vast audiences outside the arena, who generated tens of thousands of negative social media responses to Israel’s participation, staged mass protests waving Palestinian flags, and even prompted security incidents that required the involvement of Israel’s General Security Service in the host cities (Malmö, Sweden in 2024, and Basel, Switzerland in 2025) (Öberg, 2025).

As will be discussed in detail in the literature review, it is important to underscore that Israel has historically exhibited an unusually high level of public engagement with the Eurovision Song Contest. The contest has long been framed through a political lens and understood as a cultural platform that contributes to the construction of Israeli national identity. Consequently, political involvement in Israel’s Eurovision participation has been both consistent and enduring. Previous research has shown, for example, that Israel has used the Eurovision stage to project a Western cultural image, despite its far more complex cultural identity in practice (Mahla, 2022; Press-Barnathan & Lutz, 2020); that it has leveraged boycott threats surrounding the contest as a means of bolstering internal national cohesion (Rosler & Press-Barnathan, 2021); and that it views the event as an opportunity to amplify national and patriotic sentiment (Ariely & Zahavi, 2022).

Nonetheless, this study contends that even within the context of Israel’s longstanding political engagement with Eurovision, there are meaningful differences between the media framing of the contest during ordinary years and during periods in which Israel confronts significant political or security crises.

Through a mixed-method content analysis—combining quantitative and qualitative approaches—of journalistic framing in three major Israeli mainstream online newspapers with print counterparts (Haaretz, Israel Hayom, and Ynet) covering the 2024 and 2025 contests, and by comparing this coverage with that of the 2023 contest (the last held before the outbreak of the war), this article seeks to highlight broader cultural spheres often considered “marginal,” yet which underwent significant transformation in the wake of the ongoing conflict.

The significance of such an analysis lies in the growing recognition that the boundaries between political, social, and cultural spheres have become increasingly blurred. This phenomenon reflects what is often referred to as the mediatization of politics—the penetration of media logic, discourse, and practices into the processes of public decision-making and the shaping of political discourse (see also Gozansky & Lev-On, 2024). In this reality, the public agenda is no longer structured by clear topical hierarchies, such as the traditional division between “hard” and “soft” news, but rather by logics of visibility, emotional discourse, and visual representation.

Social media, of course, plays a central role in this process as well, serving as a key arena through which cultural events acquire political dimensions—and vice versa (Blasco-Duatis et al., 2019). Thus, a topic such as “Israel’s participation in Eurovision” can become relevant, and even crucial, to broader issues such as Israel’s international standing or the dynamics of the Middle East conflict. Ultimately, this study aims to join a growing body of research that examines the news framing and cultural impact of media events over time, and not merely at the moment of their broadcast (see, for example, Greenwald, 2023; Tamir & Lehman-Wilzig, 2023).

Literature Review

Eurovision Song Contest

The Eurovision Song Contest (henceforth “Eurovision”), established in 1955 and first held in Lugano, Switzerland, the following year, is one of the largest cultural and television enterprises in Europe and the world (Ginsburgh & Noury, 2008). The initiative, conceived by Marcel Bezençon—the first director of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU)—was inspired by Italy’s Sanremo Music Festival. Today, the contest is broadcast to an audience of between 200 million and half a billion viewers annually, reflecting both the power of the global television entertainment market and the continued ability of public broadcasting to serve as a mechanism for constructing collective cultural identity. This persists despite the growing dominance of internet-based communication (social networks, artificial intelligence, and various digital communication platforms) (Greenwald, 2020; Greenwald, 2023).

Although Eurovision is officially presented as an apolitical event, its history in practice mirrors profound political processes within Europe and beyond. Ideological and political worldviews have consistently influenced decision-making within the EBU (Yair & Ozeri, 2022). From its inception, Eurovision served as a symbol of postwar Western cultural unity, and during the Cold War it represented the capitalist West in contrast to the communist bloc, which was traditionally absent from the contest (except for Yugoslavia). Following the collapse of the Eastern bloc, the contest expanded to include Central and Eastern European countries, among them former Soviet states such as Russia and Ukraine (Singleton et al., 2007). In addition, the contest’s voting structure—its system of distributing points among countries—has, over the years, revealed clear patterns of regional alliances, political voting, and distinct voting blocs (Yair, 2019).

Eurovision has repeatedly become a stage for “political incidents.” One notable example is Ukraine’s 2016 victory with a song addressing the persecution of Tatars in Crimea by Russia—a reflection of the sharp geopolitical tensions between the two nations that challenged the “fantasy” of a conflict-free European cultural brotherhood. It is worth noting that this victory occurred after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, thus carrying an explicitly political message. More broadly, Ukraine has a long chronicle of politically charged representations and participation in the Eurovision (Bohlman, 2011; Meizel, 2013)—a trajectory that reached its peak with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when Russia was immediately suspended from the contest (Greenwald, 2023).

Israel began participating in Eurovision in 1973, becoming the first non-European country to do so. Its inclusion in the contest must be understood within broader cultural and political contexts, as it occurred during the 1970s expansion of the competition to include countries of the Mediterranean basin—Malta, Greece, Turkey, and later Cyprus—challenging the previously homogeneous Western European identity of the event. Israel’s participation has often been interpreted as a cultural and geopolitical act, expressing its desire to be perceived as part of the Western cultural sphere (Mahla, 2022; Press-Barnathan & Lutz, 2020; Panea, 2018).

Belkind (2010) argues that Eurovision has served Israel as a mechanism of national imagination, reinforcing its citizens’ sense of belonging to the West and, more specifically, to Europe. Accordingly, Israel’s participation—and at times, its success—in the contest has historically generated feelings of national pride (Ariely & Zahavi, 2022; Lemish, 2004; Rosler & Press-Barnathan, 2021). Over the years, Israel has won the competition four times (1978, 1979, 1998, 2018), placed second three times (1982, 1983, 2025), and placed third twice (1991, 2023). Among the most culturally significant moments in Israel’s Eurovision history was the 1998 victory of the transgender singer Dana International, a watershed in legitimizing LGBTQ representation within Israeli culture (Greenwald, 2020).

In this context, it is noteworthy that in Israel there is often an artificial epistemic distinction between the “political” and the “social,” whereas in other cultural settings this distinction is much weaker or even nonexistent (Morgenthau, 2012). Thus, issues such as national security and foreign affairs are typically categorized as “political,” while matters related to women’s status and LGBTQ rights are framed as “social.” By contrast, countries that have participated in the Eurovision—such as Russia and Hungary—have expressed negative attitudes toward the contest’s prominent LGBTQ identification, reflecting their perception of the event as inherently political, largely because of its association with the liberal values championed by Western European states (Baker, 2017). In other words, even examples such as Dana International’s victory and the contest’s increasing identification with LGBTQ culture are understood as explicitly political acts in other arenas.

Academic research on Eurovision is divided into several theoretical focal points. Yair (2019) identifies four main research directions. The first deals with the concept of “the imagined Europe” and cosmopolitanism, including the use of the contest for purposes of nation branding (Jordan, 2011). The second focuses on Eurovision as an LGBTQ phenomenon, particularly as an expression of popular gay culture (see, for example, Baker, 2017; Cassiday, 2014; Lemish, 2004; Miazhevich, 2017). The third examines the political dimensions of the contest, especially the phenomenon of “bloc voting” (Öberg, 2025; Yair, 1995; Yair & Maman, 1996). The fourth uses Eurovision as a tool for understanding broader social phenomena, such as political economy, regional conflicts, international criticism, and communicative or visual dynamics (Highfield et al., 2013; Panea, 2025).

It may be argued that this classification reflects an overly dichotomous distinction between what is considered political and what is perceived as social—a distinction that, as mentioned, is artificial or even foreign to other geopolitical spheres.

The present study primarily aligns with the fourth theoretical focus, as its main objective is to examine how external political, security-related, and diplomatic events have shaped the media framing of Eurovision in recent years. In this sense, the study draws upon critical thought concerning the interrelations between media, culture, and society, and particularly on the communication-as-culture approach, formulated in part through the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies (Regev, 2008; Carey, 1989). The study also introduces a slightly different, and perhaps unique, empirical perspective, as it seeks to broadly analyze how the Eurovision Song Contest is framed in the news media as an ongoing event rather than a single media occurrence. In doing so, it allows for the exploration of the contest’s political, cultural, and social implications beyond the mere occurrence of the event and its televised broadcast.

Framing Theory in Communication

Framing theory is widely regarded as one of the foundational pillars of mass communication research. Its distinctiveness lies in its shift away from a purely quantitative examination of exposure or representation and toward an exploration of the deeper processes through which events, social phenomena, and public figures are constructed within the media sphere. The theory’s core question is not what the media reports, but how it reports—what perspectives, interpretations, and cognitive templates it offers the public as part of the mediation of reality (Borah, 2011; Scheufele, 1999).

The term frame refers to a process of interpretive construction through which the media organizes information into coherent and abstract cognitive templates that help audiences make sense of reality, categorize events, and store them in long-term memory. Each media frame thus creates a kind of “cultural-social packaging” of the news story, transforming episodic reports into structured thematic perceptions—sometimes even habitual ones. The power of framing lies in its ability to define the boundaries of public discourse: to highlight certain elements, downplay others, and guide audiences toward particular interpretations of reality—often without their explicit awareness (Greenwald, 2020; Dayan-Gabay, 2024).

Framing theory draws, among other sources, upon concepts from social psychology, particularly the notion of cognitive schemas—stable thought patterns that facilitate the processing of new information. Similarly, the public responds intuitively to media frames; audiences recognize cues such as tone, terminology, and embedded cultural references within modes of reporting, and may even act in accordance with them, often unconsciously (Entman, 2004; Gamson, 1992).

Beyond the cognitive and interpretive dimension, scholars associated with cultural and critical approaches to communication studies view framing as a mechanism that preserves social and cultural order. According to this perspective, the media does not merely reflect reality; it also contributes to the enforcement, reinforcement, and refinement of existing norms, values, and ideological structures. James Carey, one of the founding figures of the Communication-as-Culture school of thought, argued that communication functions as a ritual—a cultural process that continuously constructs and sustains collective meanings rather than merely transmitting information. Accordingly, media framing draws upon collective meanings and shared symbols to reinforce the ways in which a society perceives itself and its world (Carey, 1989).

The convergence around media representations that emerge from such framing processes is not merely a consumer act but also a communal and cultural practice. Framing, therefore, assists in shaping a sense of identity and belonging, operating within a web of cultural, political, and social consensuses. In this context, several studies have highlighted the role of framing in constructing national perceptions and collective memory, in positioning social groups, and in reinforcing the distinction between “us” and “them” (see Kama, 2004; Greenwald et al., 2024; Nossek, 2004).

Methodology

Research Aim and Context

The central research question of this study is whether, how, and to what extent news coverage of the Eurovision Song Contest became more politicized from 2023 (prior to the Gaza War) to 2024–2025 (following the outbreak of the war). This question emerges from a broader theoretical and normative aim: to examine whether even soft news genres—such as leisure, culture, entertainment, and celebrity journalism—are susceptible to rapid processes of politicization during periods of war, conflict, or prolonged crisis.

It is important to clarify that the focus here is on the intensification of politicization, which has always been present within Eurovision as a politically charged contest (as highlighted in the literature review). Moreover, the 2024–2025 contests may not be entirely exceptional in this respect. Russia, for example, was suspended from participation in 2022, and its fraught relationship with Ukraine has long constituted one of the defining political dynamics of the competition since the early twenty-first century. Accordingly, this article aims to compare the political framing of Eurovision coverage in a “routine” year with that of years marked by heightened political tension.

Research Methods

The study employed a combined quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the media framing of three Eurovision contests—2023 (Liverpool, UK), 2024 (Malmö, Sweden), and 2025 (Basel, Switzerland)—in three major Israeli electronic mainstream newspapers with printed counterparts: Haaretz, Israel Hayom, and Ynet.

News items were collected from the first day of Eurovision week in each of the three contests until the day after the final (inclusive), resulting in a total of 24 days of news coverage. Items were gathered by searching the exact terms “Eurovision” [“erovizion” in Hebrew] or “the Eurovision” [“ha’erovizion”] within the internal search engines of the three news websites. To ensure data consistency, the results were cross-verified using Google’s advanced search function to standardize the database and confirm completeness.

The final corpus included 328 news items (news briefs, reports, feature stories, opinion columns, photographs, and caricatures): Haaretz – 35 items; Israel Hayom – 151 items; Ynet – 142 items.

It should be noted that this was not a sampling procedure but a comprehensive analysis of all relevant news items published by these outlets during the selected timeframes. As indicated in Table 1 (see Findings section), the distribution of items by year was relatively consistent, with the exception of a slight “spike” in Israel Hayom’s coverage in 2025. The complete database is available in the following link.

The research included two stages of content analysis: first quantitative, then qualitative.

- Quantitative content analysis serves to identify recurring patterns of predefined characteristics of messages and cognitive frames. It enables comparisons and statistical distribution analyses based on consistently applied predetermined criteria (Bloch-Elkon, 2003).

Within this framework, all collected items were organized into a data table with the following variables:

- Serial number (ID)

- Year (2023 / 2024 / 2025)

- Source (Haaretz / Israel Hayom / Ynet)

- Source’s ideological orientation (1 = right / 2 = center / 3 = left)

- Journalistic style (1 = popular / 2 = elite)

- URL

- Headline

- Author’s name (if provided)

- Presence of a dominant political framing (0 = no / 1 = yes)

The determination of whether an item contained a dominant political framing was based on a binary categorization derived from the primary emphasis of the headline and sub-headline. This binary coding allowed for systematic comparison across the Eurovision contests with respect to the extent of political dominance in their coverage.

The coding itself was conducted by two independent coders, and inter-coder reliability, assessed using Cohen’s Kappa, demonstrated a high level of agreement (κ = 0.93).

2. Qualitative content analysis involves a critical reading of texts to identify patterns of thought, recurring themes, and conceptual categories, accompanied by the researcher’s interpretive perspective on their normative meaning (Ponterotto, 2006). This approach generally unfolds in two stages:

- First, identifying and classifying recurring themes by drawing on examples, ideas, and guiding principles, thereby revealing systematic patterns and enabling conceptual generalization.

- Second, constructing an interpretive discussion that extends beyond objective textual description to uncover latent meanings, linking these insights to theoretical literature and the broader epistemological context (Geertz, 2008).

In this part of the study, two additional columns were added to the data table: one specifying the main theme emerging from each item and another providing a representative quotation illustrating that theme. Notably, items that lacked a dominant political dimension were still assigned to a thematic category. As shown in the Findings section, some themes were political in nature, while others were “soft”—that is, oriented toward entertainment or gossip.

The Rationale for Choosing the Corpus

Three key considerations guided the selection of the electronic newspapers used in this study:

-

- Ideological and professional diversity:

To ensure a comprehensive and reliable examination of media coverage, the three newspapers selected represent a diverse range both ideologically and professionally. Israel Hayom and Ynet are popular outlets (tending toward sensationalism both visually and substantively), with the former associated with a right-wing conservative standpoint and the latter representing a centrist orientation. Haaretz, by contrast, is an elite/quality newspaper (characterized by a more restrained and rational approach) with a clear left-wing political orientation (Greenwald, 2020; Kama, 2005).

Specifically with regard to Israel Hayom, which for years was perceived as a paper closely aligned with Benjamin Netanyahu and his government, it is important to note that following the death of its former publisher, Sheldon Adelson, in January 2021, it has often been claimed that the paper has adopted a more centrist and even more critical position toward the Israeli government and its policies. Consequently, it can be said that Israel Hayom currently bears greater resemblance to Yedioth Ahronoth than it did in the past (Cohen, 2023). - Popularity and mainstream positioning:

These three established news websites are among the most popular in Israel, attracting large annual readerships (SimilarWeb, 2025). Furthermore, all three are unquestionably considered mainstream journalistic sources. In the case of Haaretz, as with other elite newspapers worldwide, its cultural and intellectual influence extends far beyond its numerical circulation. - Connection to traditional journalism and broader media discourse:

Each of these outlets functions as the digital extension of a traditional print newspaper—two long-established papers and one that is relatively newer yet now firmly established. Consequently, their editorial lines, employed journalists, published articles, and journalistic sources reflect the broader media and political discourse in Israel, extending well beyond the online sphere alone.

- Ideological and professional diversity:

Findings

Quantitative Content Analysis

Table 1

Table 1 presents data regarding the number of items published about the Eurovision Song Contest in each year and in each newspaper, as well as the number and percentage of items in each year and outlet that contained any political framing. The bottom row of the table summarizes the share of political discourse within the coverage of each contest across the three examined years (the underlined figure below).

As shown in the table, media coverage of the Eurovision Song Contest between 2023 and 2025 experienced a substantial overall increase, rising from only 80 items published in 2023 to 96 in 2024 and as many as 152 in 2025. This indicates that the competition became increasingly dominant in the media agenda over these three years. This finding is somewhat surprising, as in times of prolonged crises one would expect news coverage to focus primarily on hard news topics such as defense, security, and foreign affairs, while soft news items—such as those concerning Eurovision—would be marginalized or receive very limited attention. However, as previously suggested, it appears that even during crises, room remains for soft news, provided that they can be thematically linked to the central issue dominating the public agenda—in this case, the war.

In examining differences among the newspapers, it is noteworthy that Haaretz, the elite outlet, diverged sharply from its popular counterparts, Israel Hayom and Ynet, in the volume of its Eurovision coverage. Across the three years studied, Haaretz published only 35 items during Eurovision week, compared with 151 in Israel Hayom (4.3 times as many) and 142 in Ynet (4 times as many). This finding is consistent with the well-documented tendency of popular journalism to devote greater attention to entertainment, leisure, and gossip—topics with heightened potential to elicit emotional responses, such as excitement or drama, among media consumers. Nonetheless, when examining the proportion of politically framed items, the differences among newspapers were less pronounced. In fact, Haaretz (40.0%) and Israel Hayom (39.0%) displayed nearly identical rates of political framing, whereas Ynet stood out to some extent, with 50.0% of its items characterized by political framing.

The most striking disparities presented in the table concern the political framing of the competition in 2023 compared with 2024 and 2025. Across all newspapers, Eurovision underwent a marked process of politicization in both its coverage and its framing within Israeli media discourse over these three years. While in 2023 only 13.7% of the items contained any political dimension—somewhat surprising given that, as shown in the literature review, Eurovision is, by its very nature, politically charged—by 2024 the share of politically framed items had risen dramatically to 61.4%. In 2025 this figure declined to 48.6%, yet it remained far above the pre-war level, indicating that full normalization had not yet occurred. It should be emphasized once again that this conclusion applies specifically to the comparison between 2023 and 2024–2025, and that in other years marked by wars or major military operations (which was not the case in 2023), it is possible that a pattern similar to that seen in 2024–2025 might also have emerged.

It is important to recognize that the 2024 Eurovision took place closest in time to the national trauma of the October 7 massacre and was “political” for additional reasons. That year’s contest was held in Malmö, Sweden, a city with a large Muslim and pro-Palestinian population, where extensive protests took place—both outside and inside the venue—against Israel’s participation. Consequently, the vast majority of media items in the examined newspapers focused not on the various elements of the competition itself (such as music, artistic performance, voting procedures, the history of the competition, gossip, or behind-the-scenes accounts), but rather on the surrounding political controversies. The 2025 Eurovision, held roughly a year and a half after the traumatic events, presented a more balanced framing: fewer than half of the items were political, although the political dimension remained prominent. In other words, based on the present case studies, a prolonged military, political, and diplomatic crisis can indeed generate the politicization of soft news; however, the passage of time appears to moderate this tendency, gradually restoring a degree of normalcy in later stages of coverage.

Table 2

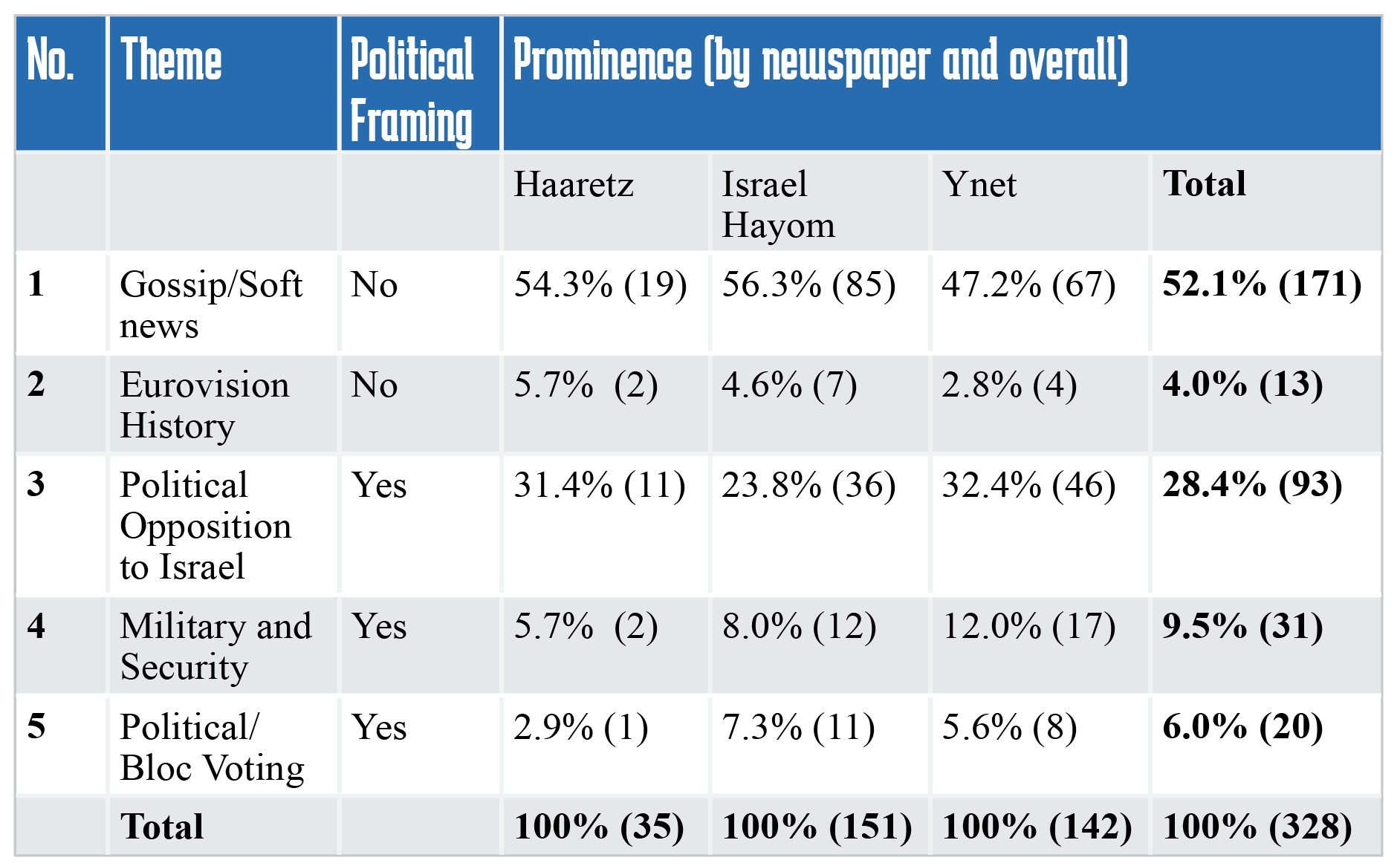

Table 2 presents a detailed breakdown of the five central themes identified in the study, the distribution of each theme according to a binary factor of political versus non-political framing, and the quantitative prominence of each theme within each newspaper individually as well as across all newspapers combined.

seen from the data in Table 2, the most prominent theme across all years is gossip/soft news, which accounted for slightly more than half of all items. This finding indicates that, despite the broader context, the Eurovision Song Contest remains primarily a popular entertainment and cultural event, even in years and situations in which the surrounding environment is highly political. This claim is reinforced by the fact that even in 2024—the most politically charged year in the sample—soft news remained highly prominent (34.3% of the items), and even more so in 2025 (48.0% of the items).

Regarding political framing, it is unsurprising that the theme of political opposition to Israel emerged as the most prominent political theme (28.4% of coverage). Themes related to military and security issues or to political/bloc voting also appeared, though to a lesser extent (9.5% and 6%, respectively). In other words, discourse centering on opposition to Israel’s participation in the contest—including calls for boycotts, suspension, and ongoing protests, both on social media and in physical demonstrations outside and inside the venue—constituted the primary components shaping the political framing of Eurovision coverage in the newspapers analyzed.

Finally, consistent with the findings presented in Table 1, Table 2 indicates that there are no substantial differences among the three newspapers with respect to the distribution of the main themes in Eurovision coverage. Just as they displayed relatively similar levels of political framing, here too Haaretz, Israel Hayom, and Ynet exhibit a comparable editorial orientation—a rather surprising finding given the well-established differences in their ideological profiles and the type of journalism each represents.

Qualitative Content Analysis

This section provides a qualitative overview, offering an in-depth description and illustration of each theme identified in the study; the quantitative distribution of these themes appears in Table 2.

Gossip / Soft News

As noted, this theme was overall the most prominent, covering over half of the news items collected and analyzed in the study. Only items characterized as “soft” content in various contexts were classified under this theme, including: coverage of the contestants in the competition; references to the ranking of different countries (primarily Israel) in online betting tables; fashion and costumes of contestants and hosts; placement of songs throughout the semi-finals and finals and the connection of this placement to chances of winning; coverage of interim results (qualifiers for the final in each semi-final); interviews with family or friends of the Israeli contestants; reporting on fan clubs; leaks of photos or videos from rehearsals; technical issues during broadcasts; references to the LGBTQ+ community and queer symbols in the contest; various non-political incidents; commentary on the hosts or hosting; and congratulations to the Israeli contestants from notable figures.

The narrative underlying the soft news and gossip theme derives from the widespread perception of Eurovision as an entertaining and fundamentally “light” cultural event. In terms of the social functions it serves, the emphasis here lies far less on national or political contexts—such as appeals to national pride, patriotism, or shared cultural symbols—and far more on escapism and amusement. This orientation naturally creates space for sensationalism, heightened drama, and, at times, portrayals of Eurovision as an exaggerated, eccentric, and somewhat detached spectacle. Such coverage often weaves together both critical and celebratory elements, consistent with the logic of a cultural “guilty pleasure.”

For example, Ynet published an article under the headline, “It’s So Bad We Love It: The Best and Worst Outfits of Eurovision” (Yoav Meir, May 14, 2023):

“The singer Käärijä, representing Finland and finishing second in the competition, left a strong impression on viewers and dominated social media with a groundbreaking stage look. He wore black pants with oversized spikes around the thighs, black-and-green shoes, and what secured him first place was a neon green puffed sleeve revealing his body, paired with a studded collar. His look was iconic, striking, innovative, and original.”

A different example of this dynamic was the clear emphasis placed on elite figures within the coverage of the contest. A recurring story—featured in both the 2024 and 2025 Eurovision—was the “traditional phone call” made by the Hollywood actress Gal Gadot (arguably the most internationally renowned Israeli today) to the Israeli contestants. This type of framing may be described as “borderline” along the soft–hard spectrum: although the focus was decidedly gossip-oriented and sensational, the very act of Gadot reaching out to the Israeli performers undoubtedly stemmed from a sense of national solidarity.

“Even Gal Gadot surprised Yuval Raphael with a video call, which the excited representative shared on her Instagram page. ‘Thank you so much, Gal!’ Yuval wrote. ‘This call gave me strength; they call you Wonder Woman for a reason.'” (Israel Hayom, Eran Swisa, May 17, 2025)

In 2024, Gadot’s remarks to Israel’s representative, Eden Golan, hinted even more clearly at the political context (albeit without stating it outright): “‘It’s amazing that you’re standing strong and steady and no one can shake you. You should be so proud of yourself!’ Gadot told Golan. ‘The best way to fight hatred is with love.’” (Israel Hayom, Eran Swisa, May 11, 2025)

The History of Eurovision

Although relatively limited in scope, this theme appeared consistently across all three years examined—four publications in both 2023 and 2024, and five in 2025. It was most prominent in the extensive, richly detailed historical retrospectives published in the days leading up to the broadcast, which functioned as a form of narrative buildup aimed at generating anticipation, heightening dramatic tension, and preparing the public for the event.

References to the past—both broadly and within the specific Israeli context—served two primary functions. First, they provided readers with a sweeping historical framework for understanding the media event prior to its airing, functioning as a kind of orientation or “viewer’s guide.” Second, they evoked and nurtured a sense of nostalgia for “the Eurovision that once was,” a contest that has undergone extensive transformation over the years: shifts in musical style, dramatic expansions in scale and spectacle, and cultural changes such as the predominance of English over contestants’ native languages.

For example, Haaretz reported:

“Israel did not yet participate in Eurovision 1963 but it did have two representatives. Carmela Corren took the stage in London on behalf of Austria with the song “Vielleicht geschieht ein Wunder,” hoping a miracle would happen. Esther Ofarim was sent by Switzerland, which will host Eurovision this year. She sang “T’en vas pas” and almost won. In the end, she settled for second place.”

(Itamar Zohar, May 12, 2025)

In a May 7, 2024 opinion column in Haaretz, Yigal Ravid—the host of Eurovision 1999 in Jerusalem—offered a characteristically nostalgic reflection on that year’s most iconic moments:

“What actually happened at the 1999 Eurovision? Everyone remembers Dana International’s dazzling performance on the walls of Jerusalem, directed by the brilliant Tzedi Tzarfati, but no one will forget her spectacular fall while holding the winner’s trophy designed by Yaacov Agam, which she was meant to present to the Swedish winner. I do not know in what state the diva was, but even as I helped her rise from the floor in the most iconic moment in the history of the contest, I was not sure she could remain standing. And so we ended Eurovision with Dana fluttering in my arms, then pulling away and fleeing the stage.”

Political Opposition to Israel

As noted earlier, among the themes characterized by political framing, this was by far the most dominant. Items classified under this theme addressed multiple forms of protest against Israel—for example: online opposition (negative reactions on social media); demonstrations in the host city (large-scale protests featuring Palestinian flags); protests outside the venue or at pre-events (such as the traditional “Turquoise Carpet” gathering of all contestants); and protests inside the arena, including extensive—almost obsessive—coverage of booing and protest chants directed at the Israeli singers during rehearsals and live broadcasts.

This theme also encompassed reports on political calls to boycott or suspend Israel from the competition—initiatives attributed to official bodies such as various governments or European public broadcasters—as well as incidents repeatedly framed by the Israeli press as “antisemitism,” whether such framing was justified, overstated, or misplaced.

At the heart of this theme lies a focus on hatred, persecution, and intra-national consolidation. Its social function stands in almost direct contrast to entertainment or escapism, drawing on sentiments that can be described as ethnocentric, foregrounding national and political symbols and markers. These sentiments, in turn, fulfill social needs related to communal cohesion, collective identity, while reinforcing a sense of belonging among media consumers. This sense of belonging may, by its very nature, rely on a dichotomous division between “us” and “them.”

Within this framework, media messages often operated visually. For instance, coverage of Eden Golan’s dress at Eurovision 2024 noted that its neckline—whether by intention or design—evoked the number 7, referencing the traumatic events of October 7. Messages were also verbal. After Yuval Raphael’s Eurovision 2025 performance, she declared “Am Yisrael Chai!” (“The nation of Israel lives on!”), a statement widely reported as a response to “antisemitism.” Israel Hayom cited activist Yosef Hadad, who posted on social media:

“Forget the moving performance, forget the amazing voice. Her shout of ‘Am Yisrael Chai’ at the end of the performance, in front of all of Europe, the haters, and the antisemites, is her greatest victory.” (May 18, 2025)

At the level of visual symbolism, another recurring framing strategy contrasted Israeli and Palestinian imagery. On the Israeli side, coverage frequently emphasized the “Israeli flag” at the Eurovision. For example, Ynet reported:

“It is important that our presence is felt and that Israeli flags are in the arena, because we must not succumb to bullying and terror.”

(Ze’ev Avrahami, May 12, 2024)

On the Palestinian side, coverage highlighted Palestinian flags and keffiyehs. For instance:

“Thousands marched through the streets of the Swedish city claiming ‘Eurovision celebrates genocide’… even one dog wore a keffiyeh: ‘Yalla, Yalla Israel – out with you!’”

(Ynet, Ze’ev Avrahami, May 11, 2024)

Another incident that received wide coverage was the performance of Swedish-Palestinian singer Eric Saade during the first semi-final of Eurovision 2024, in which he appeared onstage with a black-and-white keffiyeh tied around his arm in solidarity with Palestinians. After the European Broadcasting Union condemned the political gesture, Ynet quoted Saade’s sharply worded response on social media (Raz Shechnik, May 8, 2024):

“A former Swedish representative, who contrary to the competition rules went on stage at the first semi-final with a keffiyeh on his arm, posted a sharp response on social media against the EBU. ‘I received this “scarf” from my father as a child. I just wanted to wear something authentic for me—but the EBU thinks my ethnic background is “controversial.” That says it all about them.’”

Military and Security

This theme focuses on the interplay between military operations and wars, on the one hand, and the Eurovision competition on the other—specifically in contexts that do not necessarily involve criticism of Israel or protests against it. In this sense, the coverage explicitly links Eurovision to ‘hard news,’ particularly issues of national security. As previous studies suggest, this is not a new phenomenon. It may be assumed that by drawing such connections, journalists and reporters who typically cover entertainment, leisure, and celebrity culture heighten public interest in their subjects, thereby shifting them from the periphery toward the center of the news agenda.

It is important to note that this shift involves more than a simple reallocation of attention; it also operates as a mechanism of mutual legitimation. When an entertainment competition such as Eurovision is referenced in security-related contexts, it acquires an air of “seriousness” or depth. Similarly, security matters are perceived as more closely intertwined with the public’s daily life precisely through the medium of popular culture. This linkage between domains enables the media to blur the boundaries between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ news and to function as a cultural intermediary between spheres that are often regarded as unrelated. Although these examples come from “traditional” media, the blurring of such boundaries closely mirrors the eclectic discourse characteristic of social media. In this respect, the coverage not only increases public engagement but also conveys a vision of reality in which no topic is truly “peripheral”; rather, anything may become political—even when “wrapped in glitter.”

A clear instance of this dynamic appeared in the coverage of Israel’s 2023 Eurovision representative, Noa Kirel, in connection with a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas—a round of fighting that preceded the events of October 7:

“Noa wanted to dedicate her qualification to the final to the residents of the South… ‘I hope, through my performance and representation at Eurovision, to give them some peace and calm. And of course, security is the most important thing, and only afterward comes everything else…’” (Ynet, Ran Boker, May 10, 2023).

Kirel’s statement is particularly notable in that it presents, on the one hand, an almost seamless fusion of the two realms—entertainment and security—while on the other, maintaining a clear and explicit hierarchy between them (“security is the most important thing, and only afterward comes everything else”).

Another example emerged just moments before the Eurovision 2025 final results were announced: with the winner potentially being either Israel or Austria, a ballistic missile was launched from Yemen toward Israel. This incident prompted significant media attention that explicitly linked the two events, as reflected in Israel Hayom’s headline:

“Missile launched from Yemen intercepted—just as second place in Eurovision announced” (Lilach Shoval & Avi Cohen, May 18, 2025).

Political/Bloc Voting

This is the only political theme that does not directly concern Israel, although Israel does occasionally appear within its scope. Items included under this theme addressed questions of how bloc voting shapes the competition and the ways political considerations influence voting patterns (including biases for or against Israel). Coverage at times also examined discrepancies between public voting and jury voting across different countries.

Compared with the other political themes, this one pertains to political dynamics embedded within the competition itself, rather than political forces external to it (although these inevitably exert influence). Historically, bloc voting has always played a significant role in shaping Eurovision and the public’s perception thereof, and media coverage reflected this familiar and longstanding phenomenon.

For instance, Israel Hayom observed—possibly with a critical undertone:

“Calls to boycott Israel are only a symptom. Agendas are imposed on songs and performances, singers express personal opinions, protest voting has become legitimate, and countries that disagreed with prevailing attitudes—such as LGBTQ+ acceptance and calls for peace—were excluded or withdrew (Russia, Turkey, Hungary, and Belarus).” (Nir Wolf, May 8, 2024)

During Eurovision 2023, Israel’s representative Noa Kirel addressed both political and bloc voting through the lens of Jewish history and the Holocaust:

“Victory, for me, is receiving douze points from Poland, after all the history of my family and the people of Israel, with the Holocaust… These are the moments that truly feel like a victory…” (Haaretz, Shira Naot, May 14, 2023)

In the two “more political” competitions of 2024 and 2025, media coverage devoted considerable attention to the pronounced disparities between jury votes (which generally awarded Israel relatively few points) and public votes (which granted Israel especially high scores):

“In fact, since the introduction of the current point system in 2016, what happened tonight represents the largest discrepancy between the jury score, which gave Israel 52 points, and the public vote—bombarding Israel with 323 points, second only to Croatia with 337 points from viewers. As usual, in recent times, we were ‘a step away from victory.’” (Israel Hayom, Nir Wolf, May 12, 2024)

Discussion and Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate how a national security crisis catalyzed the significant politicization of soft news. As the quantitative analysis shows, the degree of political framing in Eurovision coverage surged from a relatively modest 13.7% in 2023 (prior to the outbreak of the Gaza War) to a peak of 61.4% in 2024—the year in which Eurovision coincided with the October 7 events—and remained relatively high in 2025 (48.6%) amid the continued conflict. This finding aligns with theories positing that crises and dramatic events have the capacity to reshape the media agenda and the operational logic of news outlets during “media storms” (Boydstun et al., 2014). Under such circumstances, even entertainment events become fertile ground for the articulation of conflicts, tensions, and identity constructions (Greenwald, 2020).

Notably, despite the pronounced rise in political framing, the coverage remained primarily (52.1%) oriented toward soft content—gossip, escapism, spectacle, fashion, on-stage mishaps, and the highlighting of sensational or nostalgic elements. This underscores the complexity of Eurovision as a media phenomenon that is both entertaining and political (Yair, 1995). It also reinforces the argument that even in moments of existential strain, audiences continue to seek “islands of disengagement” and content that is not inherently political, provided it draws on familiar cultural symbols or emotional resonance (Carey, 1989).

A comparison among the three newspapers examined reveals substantial quantitative differences in the volume of coverage, yet striking similarity in the degree of politicization. Although Haaretz—commonly associated with elite journalism (Kama, 2005)—offered much more limited coverage (35 items across three years), the proportion of politically framed content was nearly identical to that of the popular Israel Hayom (40.0% versus 39.0%). This supports the notion that even quality journalism, which typically upholds a clearer boundary between “hard” and “soft” news (favoring the former) (Lehman-Wilzig & Seletzky, 2010), may rely on political framing in cultural reporting—particularly when contextual justification exists, such as during a protracted war.

It is important to note that the finding that all three newspapers framed Eurovision in a relatively similar manner is, in fact, surprising, given the well-documented ideological and stylistic differences between them (elite versus popular press). As Table 2 demonstrates, the thematic distribution was nearly identical, especially in terms of political framing. This indicates a relatively uniform editorial approach regarding both content type (gossip versus political) and the central topics highlighted (e.g., protests against Israel, national symbols, bloc voting). These findings challenge certain assumptions in the literature suggesting that major Israeli media outlets diverge significantly in their coverage of political and social issues (see, for example, Shultziner & Stukalin, 2021). It is possible that within the context of cultural reporting during a national crisis—such as the Gaza War—a more unified discourse or “narrative consensus” emerges, transcending traditional political divides. Future research may further explore this phenomenon and the potential unifying role of popular culture in moments of national emergency.

The boundaries between “hard” and “soft” news were clearly blurred, as evidenced both by the qualitative thematic analysis and by the symbolic mechanisms identified within the texts. For example, stories such as Gal Gadot’s phone calls with the Israeli contestants simultaneously conveyed emotional support and national solidarity, while still incorporating gossip-oriented reporting about celebrities and public figures (Galtung & Ruge, 1965). Similarly, references to security events—such as missile launches during the competition—illustrate the trend of blending discourse domains and the growing prevalence of hybrid representations in social and new media (Blasco-Duatis et al., 2019). This trend appears to have permeated even more ‘traditional’ forms of journalistic coverage.

Qualitative analysis reveals an interesting distinction between the two types of framing. Non-political framing primarily generated interest through drama, spectacle, glamour, and nostalgia (Greenwald, 2020). In contrast, political framing emphasized ethnocentric, identity-based, and adversarial elements (Roeh & Cohen, 1992), including calls to boycott Israel, protests involving Palestinian flags, booing in the arena, allegations of “antisemitism” in the contest, and the highlighting of national symbols (Israeli flags, Palestinian keffiyehs, and more). As observed, political framing not only reports hostility toward Israel but also functions as a cultural mechanism for national consolidation (and sometimes seclusion) in the face of a perceived antagonistic international environment. It does so through a binary “us versus them” division—a stance particularly pronounced in ethnocentric societies (Yamaguchi, 2013). Importantly, as indicated in Table 2, this framing was consistent across all three newspapers, including Haaretz.

Another prominent theme concerned the media’s engagement with the history of the competition, which appears to have served as a mechanism of continuity and nostalgization, particularly in politically charged years. This linkage between past and present constructs a mobilizing—and at times even softening—media narrative in the face of contemporary tensions. It does so by invoking Israel’s historical continuity and success in the contest, while using retrospective items as a mechanism for building anticipation ahead of the media event (Katz & Dayan, 1985), in the positive sense of the term.

Finally, an additional theme centered on political and bloc voting. On one level, it addressed bloc voting as a general and well-established Eurovision phenomenon (Yair, 1995). On another level, it revealed the depth of public distrust within Israel regarding Eurovision’s voting mechanisms, particularly when discrepancies emerged between jury decisions and public votes. The coverage reflected a dual experience: on the one hand, a sense of alienation felt by both the Israeli media and the Israeli public; and on the other, a simultaneous sense of connection with the global audience. This reflects a distinctive Israeli vantage point vis-à-vis Europe—one that may warrant deeper investigation in future research. It is also closely connected to what scholars have described as the imagined affinity between Israel and European culture, an affinity that Eurovision both fosters and enables (Lemish, 2004; Rosler & Press-Barnathan, 2021).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that even soft news—traditionally regarded as distant from political discourse—can become a site of politicization when unfolding against the backdrop of a deep and ongoing national crisis. The case of Eurovision between 2023 and 2025 illustrates that political framing can permeate cultural and entertainment reporting while retaining a distinctly “multi-layered” character: elements of entertainment and escapism coexist with those of identity, protest, and politics. Hence, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of the interplay between media, culture, and society in an era defined by a hybrid media arena, and demonstrates that even frameworks typically regarded as “soft” are not immune to profound political influences. On the contrary, they may become central arenas for the social processing of crises, thereby reshaping their nature, function, and cultural significance.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to the journal editor, Prof. Doron Shultziner, and to the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and significant contributions to improving, focusing, and refining both the article and its theoretical arguments. Special thanks are also due to Shlomit Ehrlich for her outstanding translation work.

Bibliography

Ariely, G., & Zahavi, H. (2022). The influence of the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest on national identity: evidence from Israel. National Identities, 24(4), 359-376.

Baker, C. (2017). The ‘gay Olympics’? The Eurovision song contest and the politics of LGBT/European belonging. European Journal of International Relations, 23(1), 97-121.

Belkind, N. (2010). A Message for peace or a tool for oppression? Israeli Jewish-Arab duo Achinoam Nini and Mira Awad’s Representation of Israel at Eurovision 2009.

Blasco-Duatis, M., Coenders, G., Saez, M., García, N. F., & Cunha, I. F. (2019). Mapping the agenda-setting theory, priming and the spiral of silence in Twitter accounts of political parties. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 15(1), 4-24.

Bloch-Elkon, Y. (2003). Press, public-opinion and foreign policy during an international crisis: U.S. policy in Bosnia (1992–1995). Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University.

Bohlman, P. V. (2010). Focus: Music, nationalism, and the making of the new Europe. Routledge.

Borah, P. (2011). Conceptual issues in framing theory: A systematic examination of a decade’s literature. Journal of communication, 61(2), 246-263.

Boydstun, A. E., Hardy, A., & Walgrave, S. (2014). Two faces of media attention: Media storm versus non-storm coverage. Political Communication, 31(4), 509-531.

Carey, J. (1989). Communication as culture: Essay on media and society. London: Routledge.

Cassiday, J. A. (2014). Post‐Soviet pop goes gay: Russia’s trajectory to Eurovision victory. The Russian Review, 73(1), 1-23.

Cohen, I.D. (2023, May 9). Yisrael Hayom is no longer Bibiton, but what it is remains unclear. Ha’aretz. https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/media/2023-05-09/ty-article-magazine/.premium/00000187-ffcf-d510-ad8f-ffcf5e420000

Dayan-Gabay, O. (2024). Rape during wartime: The sexual violence on 7 October 2023 through the Israeli media. Media Frames, 26, 28–66.

Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. H. (1965). The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of peace research, 2(1), 64-90.

Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge university press.

Geertz, C. (2008). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In T. Oakes & P. L. Price (Eds.), The cultural geography reader (pp. 29-40). London: Routledge.

Ginsburgh, V., & Noury, A. G. (2008). The Eurovision song contest. Is voting political or cultural. European Journal of Political Economy, 24(1), 41-52.

Greenwald, G. (2020). “Eurovision in danger!”: Media framing of the Eurovision Song Contest in Tel Aviv as a reflection of social rifts and national anxiety. Media Frames, 19, 67–96.

Greenwald, G. (2023). The historical coverage of televised media events in print media: The case of the Eurovision Song Contest. Communication & Society, 36(4), 35-50.

Greenwald, G., Haleva-Amir, S., & Kama, A. (2024). “An out gay man in the parliament”: New aspects in the study of LGBTQ politicians’ media coverage. Media, Culture & Society, 46(1), 3-20.

Entman, R. M. (2004). Projections of power: Framing news. Public Opinion, and US Foreign Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 240.

Highfield, T., Harrington, S., & Bruns, A. (2013). Twitter as a technology for audiencing and fandom: The# Eurovision phenomenon. Information, communication & society, 16(3), 315-339.

Jordan, P. T. (2011). The Eurovision song contest: Nation branding and nation building in Estonia and Ukraine (Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow).

Kama, A. (2004). Active reading: multiculturalism and the constraints of the hegemonic discourse. In Liebes, T., Kama, A., & Talmon, M. (Eds.), Communication as Culture: The Making of Meaning as an Encounter Between Text and Reader (pp. 441–470). Tel Aviv: Open University Press.

Kama, A. (2005). Letters-to-the-Editor as a site for group identities formation. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University.

Katz, E., & Dayan, D. (1985). Media events: On the experience of not being there. Religion, 15(3), 305-314.

Lehman-Wilzig, S. N., & Seletzky, M. (2010). Hard news, soft news,‘general’news: The necessity and utility of an intermediate classification. Journalism, 11(1), 37-56.

Lemish, D. (2004). “My Kind of Campfire”: The Eurovision Song Contest and Israeli Gay Men. Popular Communication, 2(1), 41-63.

Lev-On, A., & Gozansky, Y. (2024). Mediatization and war: Introduction to the special issue on new media, protest, and war. Media Frames, 26, 9–26.

Mahla, D. (2022). Distinguished member of the Euro(trash) family? Israeli self-representation in the Eurovision Song Contest. Israel Studies, 27(2), 171-194.

Malka, V., Ariel, Y., & Avidar, R. (2015). Fighting, worrying and sharing: Operation ‘Protective Edge’as the first WhatsApp war. Media, war & conflict, 8(3), 329-344.

Meeks, L. (2012). Is she “man enough”? Women candidates, executive political offices, and news coverage. Journal of communication, 62(1), 175-193.

Meizel, K. (2015). Empire of song: Europe and nation in the Eurovision Song Contest. In Ethnomusicology Forum, 24(1), 137-139.

Miazhevich, G. (2017). Paradoxes of new media: Digital discourses on Eurovision 2014, media flows and post-Soviet nation-building. New media & society, 19(2), 199-216.

Morgenthau, H. J. (2012). The concept of the political. In The concept of the political (pp. 96-120). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Nossek, H. (2004). Our news and their news: The role of national identity in the coverage of foreign news. Journalism, 5(3), 343-368.

Öberg, C. (2025). Eurovision Song Contest: From Apolitical to Mega‐Political. Politics & Policy, 53(3), e70051.

Panea, J. L. (2018). Identity, spectacle and representation: Israeli entries at the Eurovision Song Contest. Doxa Comunicación, 27.

Panea, J. L. (2025). Audiovisual narratives of the Sami people at the beginnings of the Eurovision Song Contest (1960–1980). Cogent Arts & Humanities, 12(1), 2464370.

Ponterotto, J. G. (2006). Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept thick description. The qualitative report, 11(3), 538-549.

Press-Barnathan, G., & Lutz, N. (2020). The multilevel identity politics of the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest. International Affairs, 96(3), 729-748.

Regev, M. (2008). The Birmingham School and cultural studies as a field of thought and research: Key moments and major direction. Society, Culture and Representation (Volume 1, pp. 9–30). Tel Aviv: Open University Press.

Roeh, I., & Cohen, A. A. (1992). One of the bloodiest days: A comparative analysis of open and closed television news. Journal of Communication, 42(2), 42-55.

Rosler, N., & Press-Barnathan, G. (2023). Cultural sanctions and ontological (in) security: Operationalization in the context of mega-events. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 36(5), 720-744.

Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of communication, 49(1), 103-122.

Shultziner, D., & Stukalin, Y. (2021). Politicizing what’s news: How partisan media bias occurs in news production. Mass Communication and Society, 24(3), 372-393.

SimilarWeb. (2025). Top news and media websites Ranking: Israel. https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/israel/news-and-media/

Singleton, B., Fricker, K., & Moreo, E. (2007). Performing the queer network. Fans and families at the Eurovision Song Contest, 12–24. SQS–Suomen Queer-Tutkimuksen Seuran Lehti, 2(2).

Tamir, I., & Lehman-Wilzig, S. (2023). The routinization of media events: televised sports in the era of mega-TV. Television & New Media, 24(1), 106-120.

Weimann-Saks, D., Ariel, Y., & Elishar, V. (2024). The iron swords of the soul: Psychological variables and news consumption patterns and their relation to rumor spreading during Swords of Iron war. Meadia Frames, 26, 67-96.

World Population Review. (2025). Most hated country. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/most-hated-country

Yair, G. (1995). “Unite Unite Europe”: The political and cultural structures of Europe as reflected in the Eurovision Song Contest. Social Networks, 17(2), 147-161.

Yair, G. (2019). Douze point: Eurovisions and Euro-Divisions in the Eurovision Song Contest–Review of two decades of research. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(5-6), 1013-1029.

Yair, G., & Maman, D. (1996). The persistent structure of hegemony in the Eurovision Song Contest. Acta sociologica, 39(3), 309-325.

Yair, G., & Ozeri, C. (2022). A march for power: the variety of political programmes on the Eurovision Song Contest stage. The Eurovision Song Contest as a Cultural Phenomenon, 83-95.

Yamaguchi, T. (2013). Xenophobia in action: Ultranationalism, hate speech, and the internet in Japan. Radical History Review, 2013(117), 98-118.